Ideas have Consequences

Lessons We Ought to Learn from the Cold War

In 1989 Mikhail Gorbachev and George H. W. Bush made a declaration that the Cold War had ended. Two leaders of global superpowers had to formally inform the planet that an immense geopolitical rivalry had finally reached the finish line. This came after decades of tension, espionage, nuclear brinkmanship, and philosophical entrenchment. The Cold War rarely erupted into direct conflict between the United States and the Soviet Union, although it shaped nearly every nation on earth. The conflict grew from ideological roots that ran deeper than troop movements or diplomatic cables. The event became a clash between rival anthropologies that viewed human nature, community, and destiny through mutually exclusive lenses.

The first set of causes emerged immediately after the Second World War. Europe had been ravaged. The United States emerged relatively unscathed, with intact industrial capacity and swelling economic optimism. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union carried wounds that would have broken most nations. Entire cities lay in ruins. Millions had died on the battlefield or in concentration camps. Soviet leadership interpreted the postwar landscape through a logic of survival that quickly evolved into a logic of expansion. Meanwhile, the United States interpreted the same landscape through a logic of stability that quickly evolved into a responsibility for global leadership. These divergent impulses set the stage for tension.

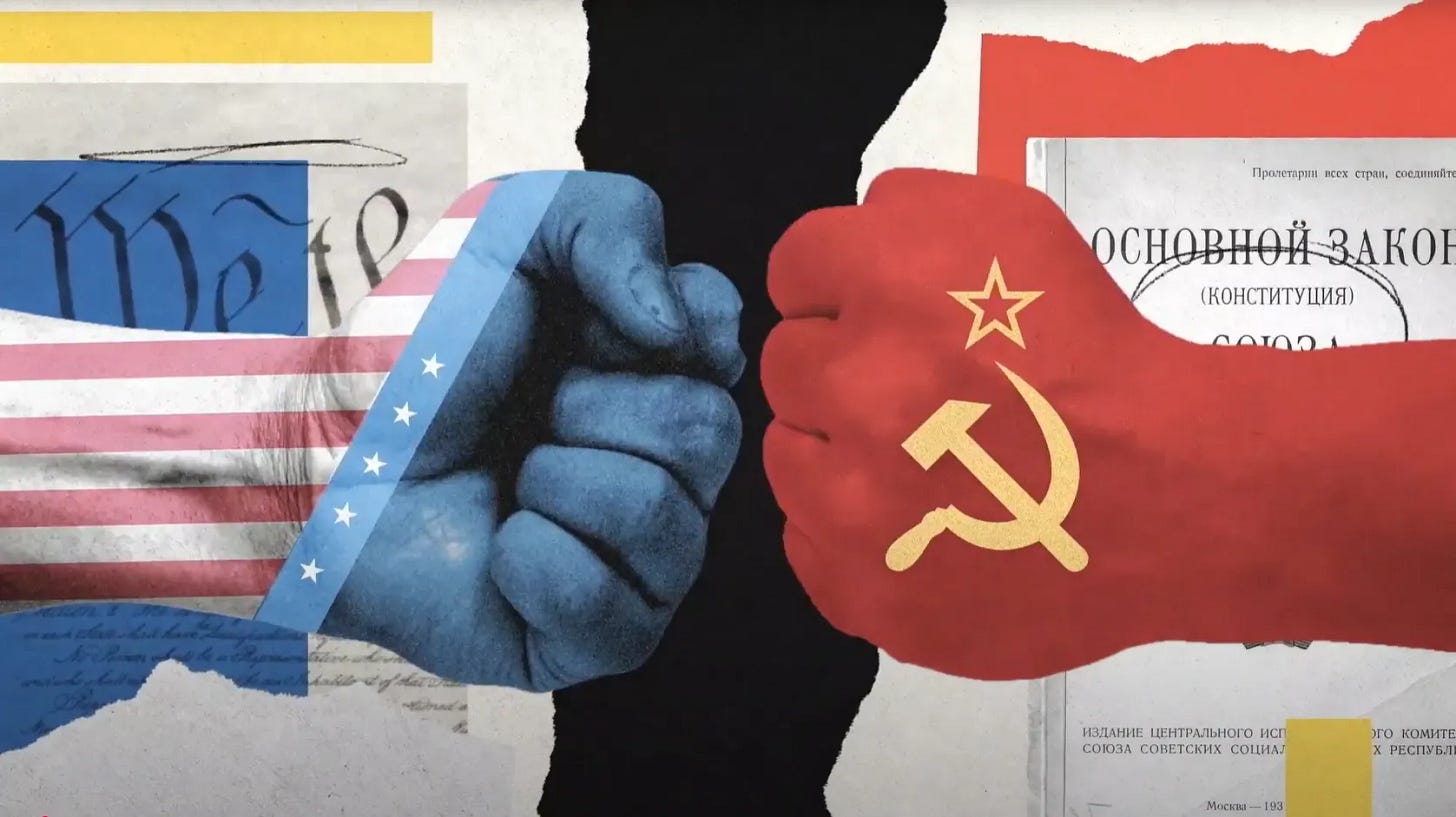

Clashing Idealogies

The deeper engine of the Cold War rested in clashing ideologies. Marxism offered a vision of history driven by material forces. Its central claim insisted that class struggle moved history from one stage to another. This vision reduced human life to economic determinism. Marxist thought viewed religion as an obstacle to human liberation. Marx famously described religion as the opiate of the masses, a description that revealed his deep suspicion of any metaphysical claim. Consequently, Soviet leadership embraced an anthropology that framed the State as the supreme custodian of human destiny. This created an ideological ecosystem in which personal freedom, private ownership, and religious commitment had little space.

Meanwhile, the American vision drew heavily from classical liberalism, natural law thought, and Christian anthropology, even in its secular expressions. The American founding era rested on assumptions that human beings possess inherent dignity. This dignity arises from a transcendent source rather than an economic process. Consequently, the American political imagination viewed the individual as a moral agent prior to the State. This belief shaped institutions, legal structures, and civic life. When a society organizes itself around a moral vision anchored in human dignity, it will inevitably collide with a society built upon materialist assumptions.

This clash did not begin in policy memoranda or missile silos. It began centuries earlier in the battle of ideas that shaped Western civilization. Richard M. Weaver, an American scholar and author, once observed that ideas have consequences, a phrase now repeated so frequently that its original potency risks dilution. Nevertheless, its accuracy remains undeniable. Destructive ideas create destructive societies. Beneficial ideas create beneficial cultures. The Cold War illustrates that philosophical assumptions rarely stay in lecture halls. They eventually shape economies, armies, foreign policy, and global power structures.

Christopher Dawson, the great Catholic historian, offered a similar insight with far greater elegance. He argued that every culture begins with a cult. A set of transcendent beliefs animates the rise of institutions and social orders. Dawson insisted that history cannot be understood without attention to the religious vision that undergirds a people’s spiritual imagination. Consequently, when a civilization uproots its religious core, the resulting vacuum demands replacement. Soviet Communism attempted this replacement. The State became the new sacred center. This created a political religion that demanded loyalty from its adherents. Its rituals, slogans, and icons attempted to mimic the cohesive power once held by the Church. Meanwhile, the American experiment retained vestiges of a Judeo Christian imagination that framed the State as a steward rather than a deity. These rival cults shaped rival cultures, which produced rival geopolitical paradigms.

Consequently, the Cold War became far more than a contest between two nuclear powers. It became a test of which anthropology could sustain human flourishing. One side claimed that freedom shaped responsibility. The other side claimed that centralized control shaped equality. One side elevated the person as a moral agent. The other elevated the collective as a historical force. These visions collided repeatedly in Berlin, in Cuba, in Vietnam, in Korea, and in the Middle East. They also collided within universities, newspapers, and artistic communities. Every textbook, television program, and diplomatic summit became a small theater where this ideological rivalry unfolded.

Eventually, the Soviet Union collapsed under the weight of its own contradictions. Central planning stifled innovation. Bureaucratic inefficiency drained resources. Citizens grew weary of surveillance, shortages, and propaganda. The system attempted to reshape human nature through coercion, although human nature proved more resilient than ideological fantasies. Meanwhile, the United States faced its own internal contradictions, although it retained enough commitment to its founding principles to weather them. In 1989, the two leaders agreed that the Cold War had ended. The declaration served as a diplomatic punctuation mark on a process already well underway. The Soviet Union’s internal decay had become irreversible.

Nevertheless, the end of the Cold War did not remove the underlying problem that produced it. The crisis began with ideas, and those ideas remain active. Marxist thought continues to shape academic culture, political activism, and social movements across the West. Meanwhile, the metaphysical assumptions that sustained the American vision have eroded. A society that forgets its transcendent foundation loses its immunity to destructive ideologies. The same materialist anthropology that once drove Soviet Communism has resurfaced under new branding. It now appears in economic utopianism, progressive social theories, and technological determinism. These movements assert that human nature changes through the right combination of coercion, policy, and scientific manipulation.

Consequently, the history of the Cold War invites reflection. It reveals that civilizations rise or fall based on the health of their core ideas. Christopher Dawson warned that societies collapse when they sever themselves from the spiritual vision that once sustained them. Many modern citizens assume that prosperity emerges from engineering, technology, or finance. Dawson would insist that prosperity emerges from the moral and spiritual imagination of a people. Without that foundation, political institutions wobble. Without that foundation, freedom loses coherence. Without that foundation, truth dissolves into sentiment.

Christians and all people of goodwill must possess a sober awareness of how easily destructive ideas spread. They appeal to the discontent, the inexperienced, and the spiritually hungry. They travel through classrooms, social media feeds, and political speeches. They disguise themselves as compassion or progress. They often appear harmless until they shape law, education, or culture. Consequently, Christians and all people of goodwill must train themselves to detect the early signs of intellectual decay.

There is a civic duty to articulate truth in the public square. Silence allows destructive ideologies to grow unchecked. A free society requires citizens who speak with clarity. A Christian anthropology offers a vision of human life that safeguards dignity, freedom, and moral responsibility. This vision sustained the West for centuries and offered the moral resources that eventually defeated the Soviet project. The same vision remains necessary for contemporary debates about identity, technology, economics, and global governance.

There is tremendous value in recognizing that the end of the Cold War did not mean the end of ideological conflict. Civilizations will always wrestle over competing visions of human nature. The only effective antidote to destructive ideas is the fullness of truth revealed in Christ Jesus. His Gospel grounds human dignity in divine love rather than economic forces. His teachings elevate freedom through virtue rather than through coerced equality. His kingdom offers a hope that no political system can fabricate. Therefore, citizens who hope for a stable and flourishing society must form their minds around His truth. They must also learn to speak that truth publicly with courage, intelligence, and conviction. Only then can society resist the pressure of ideas that aim to reshape humanity without any regard for the wisdom that shaped Western civilization in the first place.