How Luther's Revolt Shaped Our Culture

Why Catholics Must Rebuild the Toothpaste Tube

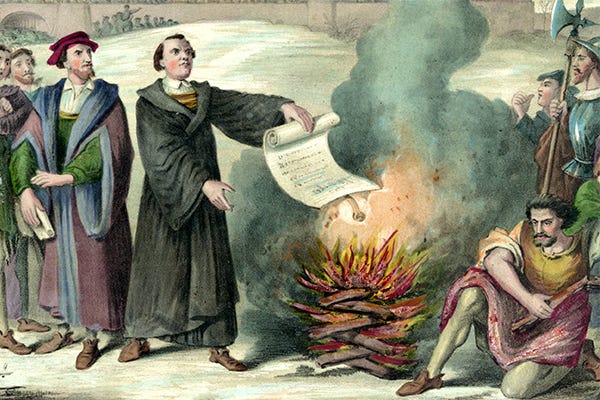

Today marks exactly 505 years since a German monk made a decision that would reshape Western civilization in ways he never imagined. On December 10, 1520, Martin Luther gathered with colleagues and students outside Wittenberg’s Elster Gate and threw Pope Leo X’s papal bull Exsurge Domine into a bonfire, along with volumes of canon law. The flames consumed more than parchment that winter morning; they ignited a revolution that would eventually lead us to our current cultural moment where moral truth has become as fluid as water.

Luther intended to reform a corrupt Church. Instead, his revolt against papal authority inadvertently opened a door that would remain permanently ajar, allowing successive generations to walk further and further from any fixed moral foundation until we arrived at today’s relativistic landscape where personal feelings often trump objective truth.

The Unraveling Begins

Exsurge Domine had given Luther sixty days to recant forty-one statements from his writings that the Church knew were doctrinally problematic. The papal bull represented the institutional Church’s final attempt to bring the rebellious monk back into line. When Luther chose fire over submission, he crossed a theological Rubicon that would have consequences far beyond his quarrel with indulgences and papal corruption.

Luther’s principle of sola scriptura seemed reasonable enough: Scripture alone serves as the ultimate authority for Christian faith and practice. This appeared to offer a corrective to the perceived excesses and corruptions that had crept into medieval Catholicism. The reformer genuinely believed he was returning Christianity to its pure, biblical foundations.

However, sola scriptura contained within itself a logical seed that would eventually flower into something Luther would have found horrifying. If individual Christians could interpret Scripture for themselves without the mediating authority of the Church, who would determine which interpretations were correct? Luther assumed that Scripture’s meaning would be self-evident to sincere believers guided by the Holy Spirit. History proved him wrong.

The Multiplication of Truth

Within decades of Luther’s death, Protestantism had fractured into dozens of competing denominations, each claiming biblical support for their distinctive doctrines. Lutherans, Reformed, Anabaptists, Anglicans, and countless other groups all read the same Bible yet reached dramatically different conclusions about baptism, predestination, church governance, and moral questions.

This proliferation of Christian interpretations established a precedent that would prove culturally revolutionary. If learned, sincere Christians could disagree about what God’s Word meant, how could anyone claim absolute certainty about spiritual truth? The door Luther had opened just a crack began to swing wider with each passing generation.

The Enlightenment philosophers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries walked through that door with enthusiasm. If religious authority could be questioned and individual reason elevated above institutional tradition, why should the questioning stop at theology? Thinkers like Voltaire, Hume, and Kant extended Luther’s principle of individual interpretation into philosophy, science, and ethics. Reason became the new pope, with each person serving as their own theological authority.

From Scripture to Self

The philosophical trajectory that began with sola scriptura accelerated through the centuries. German higher criticism applied skeptical scholarly methods to the Bible itself, treating it as merely another ancient text rather than divine revelation. Charles Darwin’s evolutionary theory provided an alternative creation narrative that seemed to eliminate the need for God altogether. Friedrich Nietzsche proclaimed the death of God and called for humanity to create its own values.

Each intellectual movement built upon the foundation Luther had unintentionally laid: the principle that individual interpretation could trump institutional authority. What began as a monk’s appeal from corrupt church officials to the pure Word of God evolved into modern humanity’s appeal from any external authority to the sovereign self.

The sexual revolution of the 1960s represents the logical culmination of this trajectory. When personal experience and individual conscience become the ultimate arbiters of truth, traditional moral boundaries lose their binding force. If Luther could defy the pope in the name of his reading of Scripture, why couldn’t individuals defy Scripture itself in the name of their personal understanding of love, authenticity, and self-fulfillment?

The Toothpaste Tube Problem

This brings us to our current predicament and the reason why so many well-intentioned efforts to restore traditional values feel like exercises in frustration. We are essentially attempting to squeeze toothpaste back into a tube that was punctured five centuries ago. The momentum of individualism, relativism, and moral subjectivism has built up tremendous force over half a millennium. Reversing that momentum through political action, cultural criticism, or even effective preaching faces the same challenge as reversing gravity.

Luther’s revolt was necessary in many ways. The medieval Church did need reform. Clerical corruption, the sale of indulgences, and the confusion of papal politics with spiritual authority represented serious problems that required correction. Yet the cure Luther prescribed carried within it a poison that would eventually prove more dangerous than the disease he sought to heal.

Conservative Christians across denominational lines often spend enormous energy trying to restore cultural Christianity to some imagined golden age. They campaign for prayer in schools, fight against secular textbooks, and organize boycotts of companies that embrace progressive social causes. These efforts, while sometimes valuable, often miss the deeper reality that the cultural foundation upon which traditional morality once rested has been permanently altered.

Wiping Off the Toothpaste

Rather than continuing futile attempts to reverse five centuries of cultural change, Catholics today need to embrace a different strategy. Instead of trying to restore medieval Christendom or 1950s America, we should focus on building something genuinely new: a culture that is authentically Christian yet uniquely adapted to our current historical moment.

This means accepting that we live in a post-Christendom world where Christianity will increasingly function as a creative minority rather than a cultural majority. Instead of lamenting this shift, Catholics can embrace the opportunities it presents. The early Church thrived as a minority movement in the pagan Roman Empire. The faith often grows stronger under pressure than under privilege.

Building this new culture requires several crucial elements. First, Catholics must develop a robust understanding of natural law Christianity that can engage secular thought on its own terms while maintaining distinctly Christian convictions. We need intellectual frameworks that demonstrate the reasonableness of faith without requiring others to accept our religious premises.

Second, we need to create alternative institutions that embody Catholic values while serving the broader community effectively. This includes excellent schools that welcome students from all backgrounds, healthcare organizations that prioritize human dignity, businesses that treat workers as collaborators rather than commodities, and media outlets that pursue truth with both rigor and charity.

Third, Catholics must learn to engage culture with confident joy rather than defensive anxiety. Instead of positioning ourselves as civilization’s last defenders against inevitable decay, we should present ourselves as pioneers of a renewal that draws from ancient wisdom while addressing contemporary challenges.

The New Tube

This rebuilt culture will differ markedly from both medieval Christendom and post-Reformation individualism. It will combine institutional authority with personal responsibility, objective truth with respect for individual conscience, moral clarity with pastoral sensitivity. Rather than choosing between tradition and innovation, it will demonstrate how authentic tradition constantly generates new expressions while maintaining core principles.

The anniversary of Luther’s bonfire provides an opportunity for Catholics to reflect honestly about how we arrived at our current cultural moment and where we might go from here. We cannot undo the Protestant Reformation any more than we can reverse the invention of the printing press or the scientific revolution. Instead of mourning what we have lost, we can focus on building what we might yet gain.

The toothpaste analogy suggests both limitation and possibility. While we cannot reverse what has already been squeezed out, we can clean up the mess and create something better than what we had before. The cultural Christianity that existed before Luther contained serious flaws that made the Reformation almost inevitable. The post-Christian culture that has emerged since Luther also contains serious flaws that make a new Christian synthesis both necessary and possible.

Catholics who embrace this challenge may discover that building a new tube proves more rewarding than trying to resurrect the old one ever could have been. After all, the Lord who promised to make all things new rarely chooses to restore exactly what was there before.