Failing New Year's Resolutions?

There is a Remedy!

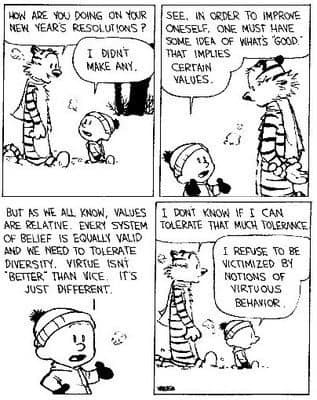

I came across this Calvin and Hobbes strip a few days ago:

What a prescient commentary on the culture! The New Year arrives with champagne bubbles, gym memberships, resolution lists, and a brief, culturally sanctioned optimism that feels both earnest and faintly theatrical. Consequently, the psychology of New Year’s resolutions reveals more about the human person than about goal setting strategies, since these rituals expose a perennial tension between aspiration and execution. Every January, human beings announce their desire to become better versions of themselves, and they do so with a sincerity that deserves more respect than it usually receives. At the same time, the annual collapse of these intentions offers a recurring reminder that willing the good and sustaining the good are entirely different achievements.

The data on resolutions is by now familiar, and therefore mildly humiliating. Studies routinely show that roughly forty to fifty percent of adults make New Year’s resolutions, and among those who do, nearly eighty percent abandon them by mid February. Within the first two weeks, a significant portion already disengages, and by summer, the resolutions survive mainly as vague self reproaches or humorous anecdotes. Therefore, the problem clearly does not lie in ignorance of what constitutes improvement, since people consistently choose predictable goals like better health, financial discipline, patience, sobriety, or order. Instead, the problem lies in the human capacity to persevere once enthusiasm fades and ordinary resistance resumes its normal strength.

This pattern invites a deeper examination of what philosophers have long called natural virtue. Natural virtue refers to those habits of character that perfect the human person according to reason, including prudence, justice, temperance, fortitude, and their many expressions in daily life. These virtues are called natural because they arise from human nature itself, rather than from supernatural infusion. In other words, every rational person can recognize them, desire them, and pursue them through the light of reason and the power of the will. Aristotle articulated this with clarity long before Christianity entered the philosophical conversation, and his influence remains visible in every serious account of moral formation.

Human beings are made for natural virtue because they are rational animals ordered toward intelligible goods. Consequently, the human person experiences a deep internal harmony when actions align with reasoned judgment about the good. Honesty stabilizes relationships, moderation preserves health, courage enables responsibility, and justice sustains social life. None of this requires revelation in order to be intelligible. Entire civilizations have recognized these truths without explicit reference to divine grace, and they have built impressive moral codes, legal systems, and cultural expectations upon them.

This explains why it remains entirely possible to live a good life without God’s grace, at least in a limited and fragile sense. A person can practice restraint, generosity, fidelity, and diligence through disciplined effort alone. History supplies numerous examples of pagans whose lives displayed admirable moral seriousness, and their achievements deserve genuine respect. Marcus Aurelius still appears on modern bookshelves for good reason, and Confucius continues to shape ethical imagination across centuries. Therefore, any serious Christian account of morality must acknowledge this natural moral capacity, since denying it would require denying the integrity of human reason itself.

At the same time, the annual wreckage of New Year’s resolutions exposes the practical difficulty of sustained virtue apart from grace. While people know what they ought to do, they routinely experience a weakening of resolve, a fragmentation of desire, and an exhaustion of motivation. The will becomes tired, attention drifts, and rational judgment loses its authority over impulse. Consequently, what initially appeared achievable becomes burdensome, and what once inspired confidence begins to provoke avoidance. This experience remains universal enough to suggest something structurally wrong within the human condition, rather than a mere failure of planning.

Here, psychology confirms what philosophy already suspected. Studies on self control consistently show that willpower behaves like a finite resource, subject to depletion under stress, distraction, and emotional strain. Habits require repetition under stable conditions, and modern life supplies neither stability nor patience in abundance. Moreover, the constant stimulation of desire through advertising and technology weakens the very capacities required for virtue. Therefore, the cultural environment itself increasingly undermines the pursuit of moral excellence, even as it continues to praise self improvement in abstract terms.

This brings us to the question lurking beneath every resolution list, which asks why the pursuit of the good feels so disproportionately difficult. Christian theology answers this question through the doctrine of the Fall, which describes a wounded harmony between intellect, will, and desire. Human beings still recognize the good, yet they struggle to choose it consistently. The moral life becomes possible, yet arduous, admirable, yet exhausting. As a result, natural virtue remains within reach, though its maintenance requires vigilance that few sustain for long.

At this point, the question naturally arises concerning grace, and therefore concerning why anyone would bother with faith at all if a good life remains theoretically achievable without it. The answer lies in the distinction between goodness and holiness. While natural virtue orders the human person according to reason, holiness orders the human person toward God. Eternal salvation requires a participation in divine life that exceeds the capacity of human nature alone. No amount of discipline can generate supernatural communion, since such communion must be given rather than achieved.

Grace enters precisely at this juncture, and its role deserves careful articulation. Grace builds upon natural virtue rather than replacing it, and it heals, elevates, and perfects what nature already desires. What once felt merely difficult becomes increasingly possible, then increasingly livable, and eventually increasingly joyful. Virtue ceases to feel like constant resistance and begins to feel like alignment with a deeper current. The moral life transforms from an exercise in endurance into a participation in love.

This progression explains why the saints consistently appear both morally impressive and strangely free. Their virtue does not present itself as clenched determination, and instead manifests as a settled joy in the good. Their wills remain active, yet they are strengthened by a source beyond themselves. Consequently, what exhausts the merely disciplined person animates the graced one. The burden remains, yet it is borne differently, since grace supplies an interior assistance that natural effort alone cannot replicate.

Here, the cultural critique embedded in Calvin and Hobbes becomes instructive. Calvin’s snarky dismissal of New Year’s resolutions mirrors a deeper skepticism about moral striving itself. He treats values as arbitrary, self invented, and endlessly revisable, which reflects a broader modern attitude toward moral claims. This posture appears clever, yet it quietly abandons the possibility of genuine moral formation. Once virtue becomes a matter of preference rather than participation in objective goods, commitment dissolves into irony.

Historically, this stance repeats a familiar pattern. Every culture that jettisons God eventually reframes virtue as subjective, negotiable, or oppressive. Moral effort then appears naïve, hypocritical, or psychologically unhealthy. Cynicism replaces aspiration, and satire substitutes for formation. Calvin articulates this instinct perfectly, even as he embodies its consequences. The joke lands because the audience already shares the assumption that sustained moral improvement remains faintly absurd.

Christianity neither denies the difficulty of virtue nor mocks the effort. Instead, it explains the struggle and offers a remedy. Grace does not excuse failure, and it strengthens the will for perseverance. It also reorients the moral life toward love rather than self optimization. The question shifts from how to become better to whom one belongs. From this perspective, virtue becomes a response to a gift rather than a project of self construction.

Therefore, New Year’s resolutions remain worthwhile, though incomplete, expressions of the human longing for order and goodness. They testify to a natural moral awareness that refuses extinction, even in a skeptical age. Their failure rates reveal the limits of unaided will, and their persistence reveals the dignity of human aspiration. Grace does not mock these efforts, and instead fulfills their deepest intention.

In the end, the annual ritual of resolutions serves as an unintentional catechesis. It teaches that goodness remains intelligible, that effort matters, and that perseverance requires help. It also reveals that holiness lies beyond technique. A good life remains possible without grace, though it remains painfully difficult. A holy life remains impossible without grace, and it becomes luminous through grace. That distinction explains why faith endures, why virtue survives satire, and why the human heart continues to reach beyond its own strength each January, even while suspecting the outcome.