A Theology of Frodo's and Bilbo's Birthdays

Tolkien's Biblical Intent for Frodo and Bilbo

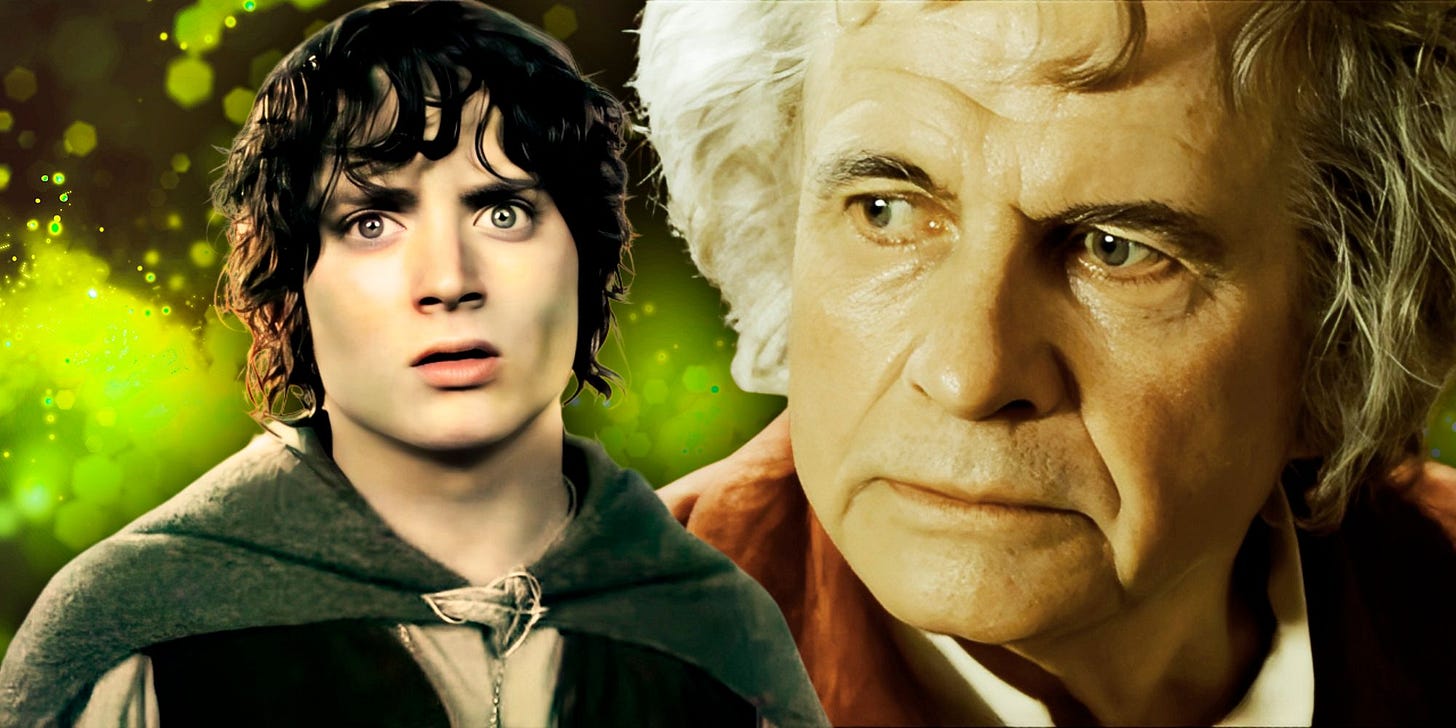

September 22 is a date that most pass by with little reflection. Yet for readers of J.R.R. Tolkien, and especially for those who know the biblical imagination behind his work, this day carries a depth of meaning far beyond the birthdays of two fictional hobbits. It is on this day that both Bilbo and Frodo Baggins, central figures in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, were born. Tolkien, who never left anything of great significance to chance, intentionally placed their birthdays on the date of the traditional autumn equinox. This was not merely a convenient date. The equinox carries with it a symbolic rhythm in salvation history, tied to biblical typology and Christian liturgical tradition. To understand this, one must see how September 22 mirrors its counterpart, the spring equinox, March 25, the traditional date of both the Annunciation and also of the Crucifixion, and in Tolkien’s mythology, the destruction of the One Ring. In the Christian imagination, the two equinoxes function as parallel markers of balance, turning points where heaven and earth meet in decisive spiritual struggle.

The autumn equinox was long linked in the Christian calendar to Michaelmas, the feast of St. Michael the Archangel. This feast celebrates Michael’s triumph over the fallen angel Lucifer, an exalted seraph who sought to exalt himself above God. According to the Book of Revelation, “Michael and his angels fought against the dragon, and the dragon and his angels fought, but they were defeated and there was no longer any place for them in heaven” (Rev 12:7–8). The irony of God’s victory lies in the fact that Michael is not a seraph, one of the highest orders of angels, but an archangel, which belongs to one of the lowest hierarchies. God in His wisdom willed to exalt the lowly so as to cast down the proud. One of the lowest hierarchies is chosen to overthrow the one who thought himself the highest. This dynamic mirrors the role of hobbits in Middle-earth. They are small, unassuming, and seemingly inconsequential, yet it is through them that the great powers of evil are undone. Just as Michael, the archangel, defeats Lucifer, the seraph, so hobbits, the simplest of creatures, become the instruments of destroying Sauron, a fallen Maia of immense spiritual might. Tolkien, a devout Catholic, made these parallels intentionally. He understood that divine providence always works through the lowly to confound the mighty.

Bilbo and Frodo’s birthdays also carry significance in their communal and theological context. In hobbit culture, birthdays are not occasions for the self, but opportunities for thanksgiving. The custom is that the one celebrating distributes gifts to the guests, acknowledging friendship and community. Bilbo’s “eleventy-first” birthday feast is an exaggerated, even comical, depiction of this virtue. His generosity is lavish, his desire to give rooted in the recognition that life and friendship are gifts to be shared. The custom reflects a profoundly Christian principle: joy comes from giving, not receiving. “It is more blessed to give than to receive” (Acts 20:35). In a fallen world that constantly distorts this principle, Tolkien provides a clear contrast.

This distortion is found most poignantly in the story of Sméagol and Déagol. On his birthday, Déagol discovers the Ring in the river. When Sméagol demands it as his “birthday present,” he perverts the hobbit custom of generosity into a justification for greed. His desire twists what ought to have been an occasion of gratitude into a moment of violence and murder. From that moment, Sméagol begins his slow corruption into Gollum, enslaved by the Ring and cut off from the joy of gift and community. The tale becomes a parable of sin. Where Bilbo’s birthday feast shows that life is meant to be shared as thanksgiving, Sméagol’s birthday murder shows that greed leads only to isolation and misery. This contrast is not accidental. Tolkien presents, in narrative form, the Gospel truth that true happiness is rooted in self-gift, while selfish grasping corrodes the soul.

Bilbo himself, however, is not without his struggles. His birthday feast becomes the stage for his ultimate test. At the heart of his life is the Ring, which he has called “my own” and even “my precious.” His attachment reveals the perennial battle against pride and possession. The Ring tempts its bearer to claim power and ownership, to center the world on the self. Bilbo’s struggle to give it up reflects the universal struggle of fallen man to let go of sinful attachments. With the help of Gandalf’s stern intervention, he surrenders it. His letting go foreshadows the central theological theme of the story: salvation comes through renunciation, not domination. Bilbo’s act of surrender becomes a decisive passing of the burden to Frodo.

Frodo’s own birthday, his thirty-third, carries an unmistakable theological weight. In Jewish tradition, thirty was the age when one could begin public ministry, and in Christian memory, thirty-three is the age of Christ’s death. Frodo, stepping into adulthood at thirty-three, is called to bear the great burden of the Ring. This is not mere narrative coincidence. Tolkien is drawing a Christological parallel. Frodo’s path will be one of suffering, sacrifice, and apparent defeat, all for the sake of the salvation of others. His thirty-third birthday initiates a passion narrative that culminates in the Ring’s destruction on March 25. That date is the hinge of salvation history. According to tradition, March 25 is both the Annunciation—the moment the Word became flesh in Mary’s womb—and the day of the Crucifixion, when the Son of God gave His life on the Cross. The Incarnation and the Redemption, the Alpha and the Omega of salvation history, fall on this one date. In Tolkien’s mythos, the destruction of the Ring on March 25 is no less deliberate. It signifies the undoing of evil by sacrificial love, the triumph of apparent weakness over the powers of darkness.

In this light, September 22 is not simply a narrative convenience but a theological counterpart. The autumn equinox reflects balance, a turning point, a preparation for the dark months of winter. In Tolkien’s scheme, it signals the beginning of Frodo’s burden-bearing, a preparation for the long winter of his passion. The hobbits, like Michael the archangel, are exalted precisely because they are lowly. They become the instruments through which the high are cast down. Their birthdays mark not only their personal stories but the providential unfolding of divine justice in Tolkien’s sub-created world.

The Christian lesson of this entire structure is manifold. First, God raises up the lowly to humble the proud. Just as He exalted Mary, the humble handmaiden of Nazareth, above all the proud of Israel, and just as He made Michael the instrument of Lucifer’s defeat, so He chose hobbits, the smallest of peoples, to bring down the great tyrant of Middle-earth. Second, true joy and life are found in giving. Bilbo’s generosity contrasts with Gollum’s selfishness, reminding us that every birthday, every gift of life, is an opportunity to give thanks through self-gift. Third, the journey of maturity is inseparable from the embrace of responsibility and suffering. Frodo’s thirty-third birthday teaches that to grow into one’s full stature is to accept the cross. To live for others is the mark of true adulthood. Finally, Tolkien’s careful choice of dates reminds us that history itself is covenantal, patterned by divine providence. March 25 and September 22 are not merely seasonal markers but liturgical signs pointing to the victory of Christ and the call for every Christian to share in His triumph through humility, gift, and sacrifice.

Thus, the birthdays of Bilbo and Frodo, far from being quaint details, are part of Tolkien’s Biblical imagination. They situate the narrative within the rhythm of salvation history. They show that even in myth, the truths of the Gospel are the only real hope for the defeat of evil. On this day, then, it is fitting to remember not only two hobbits but also the feast of Michaelmas, the triumph of the lowly archangel over the proud seraph, and the eternal truth that God delights to use the weak to shame the strong. For in the end, as Frodo’s burden shows and as Christ’s Cross reveals, salvation comes not from grasping power but from bearing it, not from domination but from gift.